« Les pensées du coeur », Paris

« Les pensées du coeur »

Résonner avec José Leonilson, Sequoia Scavullo

curated by Georgia René-Worms

So I started to pay more attention to what I was doing, to what was happening to me, to my body, my sexuality, my desires, my wishes, my anxieties, to fear. I think that’s why I specialized in talking about myself in my work.(1)

Work as the desired object

[…] I like that work realizes the desire.

I like to see my desires be realized,

to know that some others too realize their desires(2)

Exactly forty years ago, the work of José Leonilson (Brazil, 1957-1993) was exhibited in Paris for the first time(3). The artworks of this major artist in Brazilian history have only been shown a few times in France since then.

In February 2017, at 680 Park Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, I walked for the first time through an exhibition of Leonilson. He paints, embroiders, draws, and writes. He employs a narrative poetry, some very matte haiku, that are both verbal and punctuated by pictogram-like drawings. A vocabulary at once autobiographical and enigmatic, focused on raw emotions and introspective reflections shaped by intimate experiences. It is a political reading of the history of bodies converging at a moment when interpersonal relationships are being disrupted in a country emerging from dictatorship, and where the perception of bodies in society is about to be profoundly affected by the emergence of AIDS.

Leonilson is an important figure of la Geração 80 (the 1980s Generation). His early works convey a certain formalist pleasure, with vibrant colors that span large-format canvases. Over the course of the decade, he transitions toward a more minimalist style, in which narratives unfold in expanses of white space – revealing an interest in Robert Ryman, whose exhibition Leonilson viewed at the Centre Pompidou in 1981. From 1991, his formats become intimate – perhaps influenced by his extensive travels in Europe – and focus more closely on the body, as his mobility was constrained by AIDS-related complications after he learned of his infection in August of that year. In an interview with Adriano Pedrosa in the spring 1991, Leonilson emphasizes both the intimate dimension of his work and the universal scope of the emotions he conveys:

“AP: Do you think your work is a diary?

JL: Yes. The works are completely autobiographical.

AP: They are completely personal?

JL: They are completely personal. But if someone looks at this (The Game is Over, 1991), don’t you think it automatically establishes a relation with his issues? Because this is something present in everyone’s life, right? We are always experiencing disappointments in love. I keep talking about myself, about my relationships. This is the diary. But it can speak about the collective subconscious.”(4)

Les pensées du coeur (“The thoughts of the heart”), takes narrative as its point of departure, building on a feminist epistemology for which what is at stake is to consider the experience as a resource to generate knowledge(5). Understood as a time of resonance rather than a direct lineage, the exhibition brings togethers Leonilson’s works from 1981 to 1991 and more recent pieces by Sequoia Scavullo (b. 1995). Reflections on nonverbal communication lie at the core of Scavullo’s paintings and films. In her canvases, she constructs a symbolic alphabet – a new language founded on emotional transmission. With paternal roots in the Taíno people of the Carribean, Scavullo integrates Taíno dream-interpretation practices and their holistic worldview, conceiving of dreaming, imagination, and personal narrative as vital tools of healing and resistance. At Sans titre, her artworks unfold as new spaces of self-invention, to exit the male gaze while resonating with Leonilson’s own homoerotic perspective. In her film Ruler of the Land, Scavullo creates a narrative that blurs the line between reality and fiction, adopting a female gaze in which the artist – or perhaps her alter ego – bewitches the man fated to become her partner. Throughout the exhibition, there is an emphasis on skin: from spotted animal pelts to imagined portraits suggesting that feline markings can hint at alternative geographical and spiritual identities. Scavullo’s Dear Mr. President (2025) fuses Alan Turing’s concept of morphogenesis with notions of self-determination through coded symbols. Patterns reminiscent of feline fur appear alongside her secret alphabet, whispering a hidden message through painting.

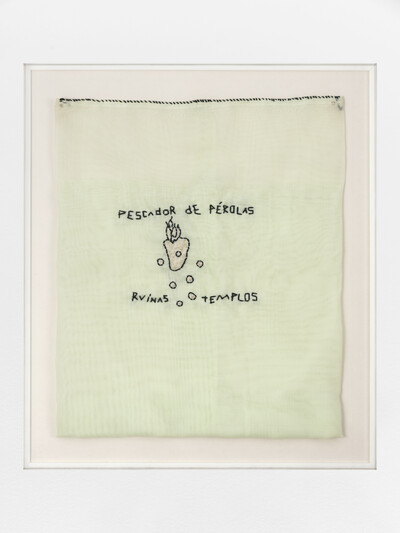

The artworks evoke a carnal language. As Roland Barthes wrote in A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments: “Language is a skin: I rub my language against the other. It is as if I had words by way of fingers, or fingers at the tip of my words.” A latent yet potent eroticism pervades Scavullo’s paintings. In If only I could sit tight inside the eagles claws (2025), a crystalline nest – almost a trap – seems to capture fluid silhouettes in which the body melds with water. Crystal palace and saliva pearls echo Leonilson’s embroideries. In Pescador de Pérolas (1991), Leonilson invokes the pearl fisher as a metaphor for an “emotion prospector”, one who dives in search of hidden truths and precious experiences linked to solitude and desire. This piece marks a period during which Leonilson intensifies his exploration of bodily and emotional vulnerability. Pescador de Pérolas also aligns with the tradition of narrative embroideries and intimate writings. Leonilson’s father was a prominent fabric merchant, and his mother a seamstress; he grew up literally playing with textiles. For him, sewing carries a double meaning: it addresses issues of gender – he once remarked: “Through embroidery, I reveal the ambiguity of my relationship to my virility.” – but it also ties directly to his interest in fashion, without aspiring to perfection. As he explained: “There are works that I begin and they start coming out badly made, and then I think. ‘I can’t try to do haute couture. This is not Balenciaga. This is my work.’ Earlier I used to think that the sewing had to be perfect. I even tried, but I took such a beating! I realized that it’s different when a fashion designer makes clothes and when an artist sews. They are two related attitudes, but really different. So I relaxed and it became a pleasure, like painting.”(6)

How do our desires emerge? What resonance with the world must they have in order to leak from us and become tangible? Is the formation of desire a deft chemistry between a constrained reality and a fictional fantasy? Do thoughts originate in the heart, or does the brain dictate them to the hear inside? The exhibition’s title is taken directly from a 1988 artwork in which the Sacred Heart’s shape is replaced by crossed swords and a brain at the center. Here, rigid, conservative religious iconography is transformed into an iconography of sentimental freedom: “I do not express myself with violence or using power. I believe the little, quiet things pierce our hearts as sharply as a bullet in the head. A gay poem seems to upset many people. I wrote a poem about a boy I met on a plane, can you imagine? I made up some of the stuff and wrote a poem on the table, including some details. … My work is a personal issue…. I think I wanted to organize my own Act Up.”(7)

“The thoughts of the heart” signifies the potential to build within vulnerable existences.

Often, we wonder how to heal or comfort ourselves, how to find an alternative to purely scientific literature, how to free ourselves from bodies in crisis. The stories of others – particularly those who have experienced illness and channeled it into art – can be effective tools for emotional support. Though our bodily narratives may differ, the strategy of making ourselves visible and proud can still unite us. Leonilson teaches us not to fear our bodies but to represent them, to give them a voice. Even though personal histories and illnesses vary, this process is about collective learning – a form of self-organization through shared experience. As Vinciane Despret writes in Our Grateful Dead: Stories of Those Left Behind: “For a while, the dead have kept a low profile, losing any visibility. Today, things could change and the dead become more active. They demand and offer their help, support or comfort… They do so with tenderness, oftentimes with humor.”(8)

Georgia René-Worms

–

The exhibition is made possible with the support of Almeida & Dale, São Paulo, and thanks to the precious help of João Paulo de Siqueira Lopes. It is part of the official program of the France-Brazil Season 2025.

(1) José Leonilson in conversation with Adriano Pedrosa (São Paulo, March 4, 1991), in Leonilson: Drawn 1975-1993, Berlin: Hatje Cantz; KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2020.

(2) Quote from José Leonilson’s statement of intent at the occasion of the New Biennial of Paris 1985 (Nouvelle Biennale de Paris). Archives from the Kandinsky Library, Centre Georges Pompidou.

(3) New Biennial of Paris, from March 21 to May 21, 1985.

(4) José Leonilson in conversation with Adriano Pedrosa (São Paulo, March 4, 1991), in Leonilson: Drawn 1975-1993, Berlin: Hatje Cantz; KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2020. Edited by Krist Gruijthuijsen, 274.

(5) Living a Feminist Life, Sara Ahmed, Duke University Press Books, 2017.

(6) Leonilson in conversation with Lisette Lagnado (São Paulo, October 30, 1992), 84.

(7) José Leonilson, interview with Lisette Lagnado, « A dimensão da fala, 1992 », in Leonilson: são tantas as verdades (São Paulo, 1995). José Leonilson refers here to [Mr. Transoceanic Express], 1990.

(8) Our Grateful Dead: Stories of Those Left Behind, Vinciane Despret, Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2015.

José Leonilson, Pele, 1983, acrylic and metallic paint on canvas, 147 × 107 cm, unique

![José Leonilson, [A noite que desce], watercolor, permanent pen, colored pencil and felt-tip pen on paper, 34 x 48 cm, unique - © sans titre](https://sanstitre.gallery/media/pages/exhibitions/les-pensees-du-coeur-paris/9d288f40da-1745420157/jose-leonilson-a-noite-que-desce-watercolor-permanent-pen-colored-pencil-and-felt-tip-pen-on-paper-34-x-48-cm-unique-400x.jpg)

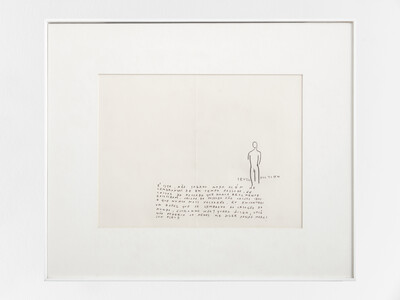

José Leonilson, [A noite que desce], watercolor, permanent pen, colored pencil and felt-tip pen on paper, 34 × 48 cm, unique

![José Leonilson, [Objetos de mártir], 1985, colored pencil on paper, 24 x 33 cm, unique - © sans titre](https://sanstitre.gallery/media/pages/exhibitions/les-pensees-du-coeur-paris/4d1c36f243-1745420157/jose-leonilson-objetos-de-martir-1985-colored-pencil-on-paper-24-x-33-cm-unique-400x.jpg)

José Leonilson, [Objetos de mártir], 1985, colored pencil on paper, 24 × 33 cm, unique

![José Leonilson, [Truth; fiction], 1990, thread and silk on linen, 31.5 x 26.3 cm, unique - © sans titre](https://sanstitre.gallery/media/pages/exhibitions/les-pensees-du-coeur-paris/5fb8adff1a-1745420157/jose-leonilson-truth-fiction-1990-thread-and-silk-on-linen-31-5-x-26-3-cm-unique-400x.jpg)

José Leonilson, [Truth; fiction], 1990, thread and silk on linen, 31.5 × 26.3 cm, unique

José Leonilson, Projeto para Catálogo, Leonilson - Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Campinas II - Página 4, 1990, permanent pen on paper, 16 × 22.5 cm, unique

![José Leonilson, [Mr. Transoceanic Express], 1990, permanent pen and watercolor on paper, 25 x 20 cm, unique - © sans titre](https://sanstitre.gallery/media/pages/exhibitions/les-pensees-du-coeur-paris/a32edf268b-1745420157/jose-leonilson-mr-transoceanic-express-1990-permanent-pen-and-watercolor-on-paper-25-x-20-cm-unique-400x.jpg)

José Leonilson, [Mr. Transoceanic Express], 1990, permanent pen and watercolor on paper, 25 × 20 cm, unique

Sequoia Scavullo, It’s like I have ESPN or something. My breasts can always tell when it’s going to rain, 2025, oil on canvas, 60 × 60 cm, unique

José Leonilson, Do. Don’t have work it., 1991, thread, acrylic, canvas, and buttons on voile, 40.7 × 26 cm, unique

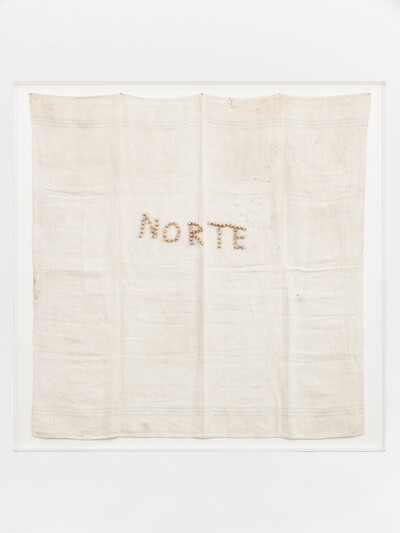

José Leonilson, Norte, 1991, beads on cotton napkin, 61 × 61 cm, unique

José Leonilson, O pescador de pérolas (Pearl Fisher), 1991, thread and metallic paint on voile, 36 × 31 cm, unique

Sequoia Scavullo, Dear Mr. President, 2025, oil on canvas, printed silk, printed cotton, unique

Sequoia Scavullo, Ruler of the land (video stills), 2025, video 16mm, 12min, edition of 3 + 2 AP

Sequoia Scavullo, Ruler of the land (video stills), 2025, video 16mm, 12min, edition of 3 + 2 AP

Sequoia Scavullo, If only I could sit tight inside the eagles claws, 2025, oil on canvas, printed cotton, printed holographic paper, unique

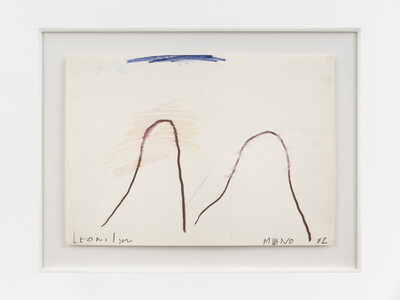

José Leonilson, Duas montanhas, 1982, oil painting and colored pencil on paper, 34 × 47.5 cm, unique

José Leonilson, Os pensamentos do coração - miniatura, 1988, felt-tip pen on paper, 8.4 × 10 cm (unframed), unique